Cult director Takashi Miike has been the subject of a lot of debate around the Tor offices lately. Unfortunately the resident haters don’t possess the mighty blogging power that has foolishly been bestowed on yours truly, so they’ll have to register their dissenting opinions below the fold, preferably in tart, choicely-worded nuggets of snarkery. My own personal obsession with the cult director has been going on for about ten years now, ever since Audition and Dead or Alive were released in the U.S. The latter is one of the most violent yakuza films in the history of the genre; the former features the most terrifying combination of acupuncture needles, hot girls, and piano wire ever committed to film. I was weirded out. I was disturbed. I was completely fascinated. It wasn’t until the release of Ichi the Killer and The Happiness of the Katakuris in 2001, however, that I came to appreciate Miike as more than a supremely gifted purveyor of ultraviolence. In particular, The Happiness of the Katakuris, with its mind-blowing pastiche of genre and B-movie conventions was like nothing I’d ever seen before…

Imagine The Sound of Music reimagined by Alfred Hitchcock if he’d been force-fed a sheet of acid and unleashed on rural Japan. But with a karaoke sing-a-long. And dancing corpses. It’s like that. But weirder.

The idea of Miike directing family entertainment seems perverse, if not utterly ridiculous, given the fact that he’s built his reputation on the dizzying extremes of his spectacularly choreographed violence and the liberal and kinkily creative use of blood and gore. If you’ve never seen a Miike film, let me put it this way: he makes Dario Argento look like a timid amateur; he makes Sam Peckinpah look like Penny Marshall. His movies have been markerted accordingly: a fair amount of buzz was generated when promotional barf bags were distributed to audiences as a (probably tongue-in-cheek) precautionary measure when Ichi premiered at the Toronto Film Festival.

And yet The Happiness of the Katakuris really does work as a family film on some strange level. Despite being correctly described as a horror/comedy/farce, Miike manages to present the Katakuris as a family which weathers all kinds of absurdity (did I mention the dancing corpses?) with an oddly touching optimism—he treats their relationships with a realism distinct from the rest of the film, so that the characters, disfunctional as they are, provide warmth and humanity in the midst of the inspired insanity unfolding around them.

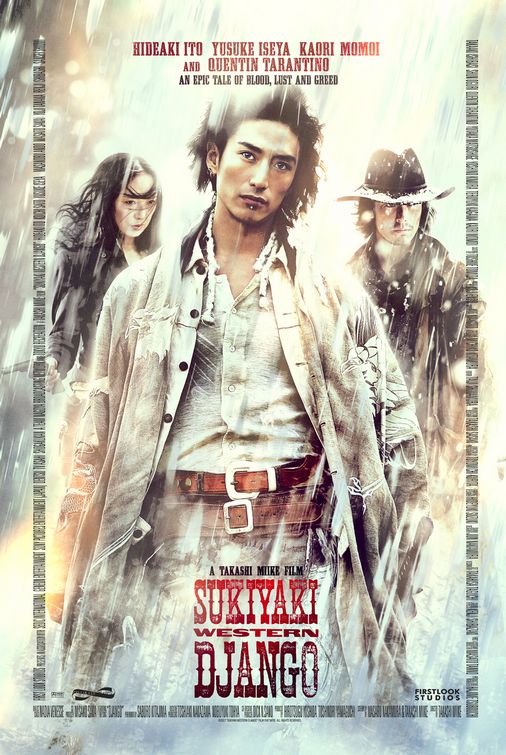

The wackier, farcical elements that characterize Miike’s “lighter fare” (like The Happiness of the Katakuris or 2004’s goofy superhero flick Zebraman) are less evident in his most recent U.S. release, the jawdropping Sukiyaki Western Django, a brilliant reworking of a Sergio Corbucci spaghetti western by way of Akira Kurosawa. In this case, the elements Miike is toying with will be instantly recognizable to even the most hardcore Western fan—the kind who will stare you down for bringing up Westworld and might punch you in the mouth for even mentioning Paint Your Wagon. The bare-bones plot centers on a mining town beset by rival gangs—the Reds and the Whites—warring over hidden gold, as well as a wronged woman and the arrival of a lone gunman with a tragic, mysterious past.

The film has received some extra publicity from the fact that Quentin Tarantino appears in a dual role as narrator and as an aged gunslinger. Tarantino, who has called Miike “one of the greatest directors living today,” seems content to play the role of fanboy John the Baptist to Miike’s Messiah of the Crazed Pastiche—the two directors clearly share a vision of film as pure, pleasurable entertainment and a penchant for deconstructing genre films and reassembling them as bizarre, maniacally clever hybrids.

In Sukiyaki Western Django, Miike takes the aforementioned stock elements of the epic Western and embeds them in levels of strangeness, constantly disrupting and alienating our recognition of the familiar plot and characters in several key ways. First of all, and most obviously, he has the audacity to set a Western in feudal Japan—specifically, the Genpei Wars of the 1100s. In a way, this represents a logical, if somewhat twisted, progression: Kurosawa drew upon Shakespeare in Ran, and was in turn an inspiration for the classic western The Magnificent Seven (which can be considered a remake of Shichinin no samurai). Miike pays homage to both strains of influence here, albeit in a hyper-literal sense: at one point an overzealous leader of the Red Gang reads (an extremely anachronistic copy of) Henry V, and recognizing the parallels between his situation and the War of the Roses, rechristens himself after the title character. Later in the film the leader of the White Gang, a samurai swordsman dressed like a Tokyo clubkid version of David Bowie in Labyrinth, faces off against the hero, a six-gun-wielding, duster-wearing man-with-no-name-type in a High Noon-style confrontation that completely transcends genre, catapulting the film into the realm of pure fantasy.

In addition, although the film is in English, none of the Japanese cast speak the language fluently—Miike had them learn the script phonetically, which makes for some understandably stilted, jerky cadences. Even Tarantino, the only native English speaker in the movie, delivers his lines in a bizarre mixture of gruff gunslinger twang and the Zenlike patois of a kung-fu master. The removal from reality into the surreal is just as evident at a visual level; on a stark landscape composed of not much more than sky, dirt, and gravestones, Miike paints with a pallet of deep, brilliant reds and incandescent whites; his images possess an almost hallucinatory beauty that gain in intensity throughout the film, culminating in a final bloody showdown in falling snow that is indescribably breathtaking.

And yes, for those familiar with the quirks of Miike’s oeuvre, there is also a gratuitous, albeit brief claymation sequence thrown in for no real reason at all. Why not?

The brilliance of Sukiyaki Western Django lies in the fact that even as it seems to parody the conventions of the Western epic—from its stock characters to its predictable dialogue to the overly-familiar twists and turns and the inevitability of its conclusion—is that in doing so, the movie reinforces the sheer pleasures of epic drama by stripping them down to the most basic levels and recasting them in such a novel and deliberately surreal light. Purists and other people who prefer their movies to adhere to conventional formulas probably won’t appreciate the delirious slicing, dicing and mashing that Miike perpetrates across the grizzled face of the Western. Personally, though, I’ve never understood the fun in being a purist. Though it might seem an odd comparison, I enjoy Miike’s films for the same reason I love the work of Alan Moore or Neil Gaiman—all three are hyper-referential and allusive, stripping the mythic into shreds and reweaving the fragments into their own strange tapestries, telling old stories in new ways, violently yoking together characters and conventions and generic elements until they work in ways they’ve never worked before. Okay, granted: when Gaiman and Moore call upon Shakespeare, the results are usually a little less crazed, violent, and manic, but in its way, Miike’s vision is no less inspired.

Enough prelude: behold the trailer—also known as the most awesome thing you will see all day:

I wish I could say that Sukiyaki Western Django will be Coming Soon To A Theater Near You, but chances are it won’t be (it premiered in New York and Los Angeles in late August/early September, although it has yet to hit Europe as far as I can tell). On the bright side, the DVD is available on Netflix, Amazon and similar sites. Miike’s films are not for everyone, but even his detractors have to admit that they leave an impression like nothing else, and that’s rare enough to be worth experiencing once in a while (and if you find that you disagree, please do enjoy the comment option below…)

Finally, io9 reports (in a post excellently titled “Time Travel Superhero Comedy Yatterman from Japan’s Most Psychotic Director”) that Miike’s next project seems to be a return to the lighter stuff. Slated for next spring, it’s a live-action adaptation of a late 70’s anime—but don’t the mention of adorable robot dogs fool you. Whatever happens, I promise you: There Will Be Crazy, and it will be warped and wonderful and I, for one, can’t wait.